Why Do People Hoard Information Processing Piles as Works of Art

Animals similar to hoard. Christopher E. Overtree, manager of the Psychological Services Center at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and a specialist in treating hoarding, says that "the mechanisms triggering this kind of biological reflex are present in all of us." A friend of his in Minnesota had an hawkeye'due south nest on his belongings fall from a tree. This led to a surprising discovery: 23 canis familiaris and cat collars. "The hawkeye ate the animals simply saved the collars," says Overtree. His own cat, Gus, wasn't much better. Overtree recently tailed his cat sneaking off with his married woman's costume jewelry, dragging the trinkets into the attic and stashing them in a hole in the flooring. "I realized he must be saving it," says Overtree. "I think it is interesting to see a behavior that has no practical value in an animal."

Hoarding, some scientists suggest, is a sensible activity to have in an uncertain world. "We have been shaped past evolutionary pressures in the past to bargain with resources scarcity, and hoarding is one of those possible strategies," says John L. Koprowski, professor of wildlife conservation and management at the Academy of Arizona and an authorization on squirrels. He refutes the conventional wisdom that squirrels only gather what they need to survive winters. Studies of eastern grayness squirrels, for instance, suggest that up to 74 pct of buried acorns are never recovered. They could be lost—or merely stored, simply in instance.

The eagle ate the animals but saved the collars.

While saving up in this mode seems both sensible and prevalent among animals, it is a bona fide disease among humans. This year, for the first time, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM—the bible of psychiatrists and insurers—listed it as a distinct disorder. Information technology is too ane with serious consequences, with the potential to ruin relationships, upshot in evictions, and fuel lethal fires. And according to the American Psychiatric Association, 2 to 5 percent of the U.s.a. population suffers from it.

After all, we are being pushed to eat. "Contemporary U.South. households have more possessions per household than any gild in global history," explains Jeanne East. Arnold, professor of anthropology at the Academy of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). In 2012, Arnold and a team of sociologists and anthropologists published a book, Life at Home in the 20-First Century, based on a four-year report of 32 middle class, dual-income families in Los Angeles. The authors found that 75 percent of families banished their cars from garages "to make fashion for rejected article of furniture and cascading bins and boxes of more often than not forgotten household goods." Superstores like Costco, they argued, have increased our trend to stockpile food and cleaning supplies—and the result at abode is stress. Women who described their homes every bit cluttered had higher cortisol levels—a sign of stress—than those who didn't.

The line between hoarding, the mental disorder, and hoarding, the bad habit (or natural tendency), is worth considering. Does saving your children's finger paintings from 1982 mean you have a de-acquisitioning problem? What well-nigh those boxes of clothes sized 30 pounds agone in your closet instead of at Goodwill? The popularity of hit reality shows like Hoarders and Hoarding: Cached Alive is surely due in function to the fact that we see ourselves in fifty-fifty the well-nigh extreme cases. The boundaries of this fence reveal something nearly who we are equally people.

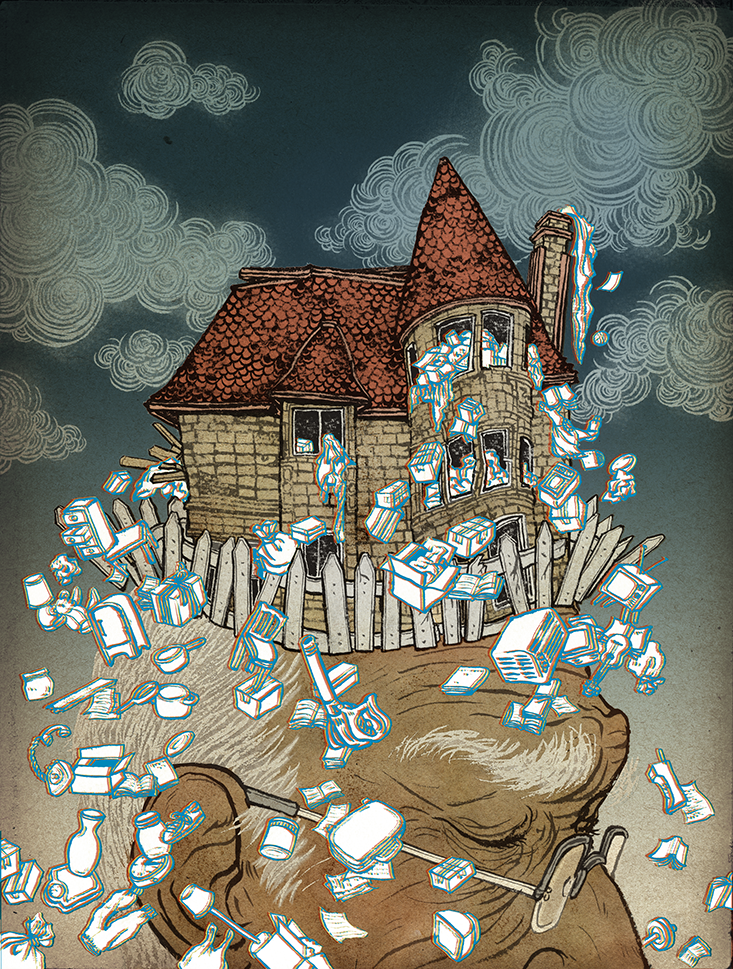

Onorth a tidy street in a resurgent New England mill town, where the trimmed bushes expect like green thimbles mounted in mulch, Melvin's large Victorian house sticks out. Two bicycles, i missing the front wheel, lean against threadbare front end steps; stacks of two-by-fours, rakes, and bicycle tires piled up on a desk-bound surround the front door. Melvin, an erudite lawyer in his late 60s who requested a pseudonym, wears khakis and a pressed blueish-and-white shirt with neatly rolled upward cuffs, looking a bit like the tardily Canadian actor Conrad Bain. He speaks fluent French and can go by in Russian. He nimbly chats nigh Robert Pinsky one minute and Oriana Fallaci the next. The divorced father of two is quick with a joke or a boast most his children. He loves to bake, particularly Linzer tortes.

Melvin hasn't invited anyone into his home in more than a year; he reveals this while leading me, single file, through piles of possessions on narrow paths, known in hoarder parlance equally "caprine animal trails." Cans, dishes, and mugs coating kitchen countertops. He hands me a laser pointer so I can ask most his many inaccessible items equally we stroll through the house. We encounter roughly 200 musical instruments in diverse states of repair, scores of VHS tapes, racks of dress shirts, vintage radios, several skis, a dozen or so motorcycle helmets, and countless books—some in barrister bookcases, others in boxes. He owns a valuable watercolor by Whistler every bit well as a worthless stuffed blue parrot that looks like a carnival prize.

Melvin says he can remember a time before the clutter crept up on him and the house was "lite and blusterous." He bought his identify virtually twenty years agone after a bitter divorce and soon found a housemate he enjoyed socializing with. He hosted habitation-cooked dinners and raucous dance parties, but after his housemate moved out, stuff moved in. "Slowly it got filled up floor to ceiling," he says. Melvin, nonetheless, insists that he is non a hoarder. "I don't think of it as hoarding at all," he says. "That implies greed, one of the medieval sins. It's really an accumulation of stuff, and information technology happens because I have an centre for everything under history." Simply, I ask, wouldn't he admit his collecting has gotten out of manus? He thinks about it and responds, gently, "I accept a problem de-acquisitioning things."

Melvin hasn't invited anyone into his home in more a year; he reveals this while leading me, unmarried file, through piles of possessions on narrow paths.

Is Melvin's self-diagnosis right? Is he actually a quirky, but normal, collecting enthusiast with a particularly strong attachment to what he judges as treasures? Probably non. In fact, information technology is this very human feeling of attachment which is the first step in a hoarding disorder. Randy O. Frost, a professor of psychology at Smith Higher, and coauthor ofStuff: Compulsive Hoarding and the Meaning of Things, saw this extreme attachment form in real time, in a set of psychology experiments involving a rather unexciting collectible: Key chains. He distributed key chains to both hoarders and non-hoarders, asking each group to rate their zipper to the trinket during the course of a week. He expected the connectedness to grow gradually. "That didn't happen," he recounts. "[Hoarders] had itimmediately. It told me something nearly the way in which attachment occurs, that it happens immediately on ownership."

Attachment becomes strengthened past forgetting that the object is just an object. Carolyn Rodriguez, who directs the Hoarding Disorder Enquiry Program at Columbia University, says some of her clients assign man qualities to objects. "For many patients, the master relationship in their lives is not with another person," she observes. "Instead, it's a relationship they accept with their stuff—and their stuff is what they turn to for companionship and condolement." The objects can serve as a stand up-in for a person. "People volition pull a agenda from 2002 out of a box and cry at how securely that calendar connects them to the things they did in 2002, or the people they loved in 2002," says Overtree, the Amherst psychologist. Discarding something stops existence a uncomplicated or rational act.

Those with hoarding disorders, then, take an amplified sense of something that all of united states of america cherish: Our deepest feelings for our families and shut friends, and our artistic sensibilities. On the second flooring of Melvin's business firm, he has half-a-dozen pairs of cowboy boots in boxes, just he owns many more. "This isn't my Western boot room," he jokes. He has a thing for the Luccese brand—"the all-time American cowboy boots" in his opinion—and so he buys them at grand sales, flea markets, and thrift shops. "I'll choice them up for any friends I accept that might be that size," he says. Melvin's daughter says that her begetter is ane of the most generous people she knows, just he obviously amasses more than gifts than he has potential recipients.

While Melvin's firm is overstuffed, many of his books, vintage radios, and musical instruments mean the world to him. "I appreciate the craftsmanship and the beauty that goes into them," he says. "Everybody else has an iPhone and walks effectually being governed by an iPhone. For me it's objects, and I dearest them."

Overtree says people who can't part with their possessions often come across an inherent beauty in them. And that's a quality he doesn't want to tarnish. "I take been trying to figure out where is the sugariness spot between curing somebody and helping them live a happy and productive life," he says. Dazzler is a unsafe thing, another psychologist told me. How do we concur onto the things that we dear and cherish without being overwhelmed by them? How do we learn to allow go?

There is, even so, a second component to hoarding disorders that has less to do with an distension of what makes us human being, and more to exercise with a diminishment. Psychiatrist Sanjaya Saxena of the Academy of California, San Diego, found that patients with compulsive hoarding syndrome showed "diminished activeness in several parts of the cingulate cortex," the part of the brain that governs motivation, executive control, and response to conflict. Phil Wolfson, a psychiatrist based in San Francisco, told me patients with hoarding problems "are frequently depressed, they are oftentimes isolated socially or socially phobic, or they are obsessive-compulsive people; they have all kinds of other habits, difficulties, and anxieties."

"I don't think of it as hoarding at all. That implies greed, one of the medieval sins. It's really an accumulation of stuff."

But some of the same brain areas that are underactive nether normal circumstances become hyperactive when hoarders are confronted with their possessions. David F. Tolin of the Yale Academy School of Medicine asked participants in a report to decide whether their old papers can be shredded, while monitoring their brain activeness. He found that hoarders' brains zoomed into overdrive like a seismograph measuring an earthquake—compared to salubrious controls. (That didn't happen when they watched someone else's papers existence ditched.) "The parts of the brain involved in helping you judge that something is important are kicked into such overdrive that they are maxed out, so everything seems of import," Tolin explains.

Monika Eckfield, a professor of physiological nursing at California State University, San Francisco, concurs that many hoarding patients struggle with processing information. To avoid the anxiety of throwing something abroad, they simply put off the decision to do so. "This is mutual to all of us," Eckfield says. Like the neuroscientists, she believes hoarding becomes abnormal equally a upshot of "mis-wiring" in the brain's executive functions. Chronic hoarders "have a much harder time following through," she says. "They become distracted. They get disorganized. They end up calculation to the pile, and the idea of sorting through those piles is very overwhelming."

Godern science has clearly revealed why hoarding deserves the designation of "disorder": It is reflected in concrete differences in how the brain is wired. At the same time, it is something that reflects to us some of the qualities and decisions with which we all struggle: Consumerism, attachment, decision-making, time management—and, at some level, survival. I'1000 left wondering if it is any coincidence that it was in 2013, when society demands so much from us in each of these capacities, that hoarding has taken on full-fledged disorder status in the DSM-V handbook.

David Wallis has contributed to The New Yorker, Wired, Esquire, The New York Times, and other publications. He is also the editor of Killed: Not bad Journalism Too Hot To Print, and Killed Cartoons: Casualties from the War on Free Expression.

Source: https://nautil.us/is-it-normal-to-hoard-1720/